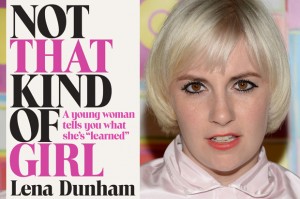

Lena Dunham’s “Not That Kind of Girl” breaks the traditional mold for celebrity autobiography styles.

Celebrity’s producing autobiographies is a prominent trend in today’s publication terrain; it borders on expected. However, in the case of Lena Dunham’s Not That Kind of Girl, the expected mold of autobiographies is broken, according to an article recently completed by The Boston Globe. Fundamentally, the composition of the book outside of the normal; the content is comprised of twenty-one essays, including a smattering of miscellaneous items, such as lists and humorous email exchanges. The essays and miscellaneous content are separated into distinct sections—love and sex, the body, friendship, work and the “big picture.”

Dunham earned her right to produce an autobiography, completing a successful independent film and spearheading her own semi-autobiographical television show entitled Girls, all by the age of twenty six. These two successes alone were enough for Dunham to reportedly earn a three and a half million-dollar advance for the book. But, as a result, the voice of her Girls character—Hannah Horvath—can often be hard to separate from the voice that is present in her autobiography, and those differences that do exist can present some issues for die-hard Girls fans. There are, of course, many commonalities. For instance, Dunham’s signature mannerisms are transferred quite easily to the autobiographical terrain, specifically the tension she feels between helpless disclosure and exerting complete control. Much like Horvath, Dunham exhibits a flip, goofy and self-deprecating humor in the autobiography. However, unlike the television character, Dunham’s writing in the book clearly demonstrates a woman in full possession of her faculties and an awareness of her place in the world.

The article particularly notes a section entitled Girls and Jerks, which details the attraction of women to men who treat them badly. Dunham explains her own attraction to this path as a possible reasoning. She disclaims that she had a lovely childhood, including a family that never really had many worries or concerns. As a result, when she got to college, she realized just how sheltered she had been up until that point. To understand those who had suffered, she believes she subconsciously sought out “jerks.” However, Dunham acknowledges that this choice is flawed, of course; a mistreating man is nothing compared to living in a war zone. In general, the article notes that Dunham experiences the most success in chronically her childhood with her typical sense of humor. Alternatively, Dunham’s writing is least appealing when she attempts to hand out advice, particularly due to her young age and limited experiences.